...free operating systems based on Linux have never been found guilty of patent infringement, making Linux a patent-tax-free alternative to Windows. Not only do these free software systems have no patent tax, they have no taxes whatsoever, because — like all open source software — they are available to the public at zero cost.

|

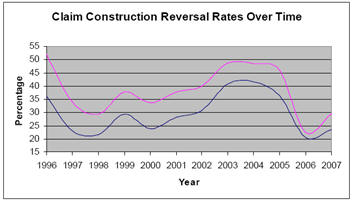

An Empirical Study of Claim Construction Rates (permalink) In an upcoming article in the Michigan Law Review entitled Practice Makes Perfect? An Empirical Study of Claim Construction Reversal Rates in Patent Cases (SSRN download page.) David Schwatrz investigates whether U.S. District Court judges "with more claim construction experience fare better on subsequent appeal." "Surprisingly," Mr. Schwaz concludes (rather harshly), "the data do not reveal that district court judges learn from appelate review of their rulings."

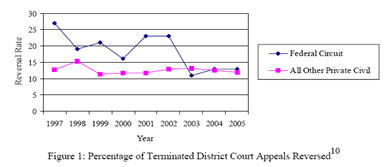

Since the U.S. Supreme Court decided in Markman v. Westview (Cornell University Law School) in 1996 that claim construction is a matter of law, the issuance of a so-called Markman ruling has become a standard feature of patent litigation in the United States. As Schwartz noted "previous studies have shown that the Federal Circuit reverses decisions on the issue of claim construction at an alarming rate" citing Kimberly Moore's (now somewhat dated) 2001 empirical study that showed district courts wrongly construed 34,5% of claim terms and that "29,7% of the judgements entered in cases had to be reversed or vacated because of erroneous claim construction." In his article, Reversing the Reversal Rate (Fordham University pdf), Paul M. Schoenhard challenges the "pervasive perception that the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit reverses district court rulings in patent cases at an inordinately high rate."

Noting that there has been "a precipitous drop in the Federal Circuit's reversal rate over the past 8 years - stabilizing at 13% in 2004 and 2005", he concludes that the "Court's reversal rate has fallen in line with other courts of appeal." More Patent Nonsense (permalink)

Thus, Ted Clark, senior vice president and general manager of the Notebook Business Unit, Hewlett-Packard (1 page pdf) writing for the hometown Houston Chronicle Throwing his support behind the Patent Reform Act of 2007, Mr. Clark warns "If our patent system isn't updated, the consequences could be loss of innovation and jobs." Loss of innovation and jobs? According to U.S. law (35 USC 101) patents may be granted on "any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof." Patents and innovation go hand in glove. As of this Tuesday past, USPTO records indicate that Hewlett-Packard has received a total of 17,804 U.S. Patents. Since 2000. Hewlett-Packard has more than doubled the number of patents it receives from the U.S. government. Hewlett-Packard, the company that attaches the word "invent" to it's Trademark - has been among the top ten orgainzations receiving U.S. patents for more the letter part of a decade. It would appear that HP is more innovatiove than ever, so it is somewhat curious that Mr. Clark argues that the "PRA would also address the need for effective and timely methods for patent review that will weed out bad patents in the system and cut down on need for immediate litigation." Would this result in fewer patents being issued to HP? Or is Mr. Clark, like his colleague Bruce Sewell at Intel, concerned about his employer's bottom line?

The cost of infringement is going up. But isn't this expected? In industries where profits are derived from intellectual capital, intellectual property rights (IPRs) play a more dominant role in the realisation of these profits. There is certainly an abundance of empirical evidence to indicate that IPRs are assets of increasing business value. Isn't it to be expected that the cost of infringing these IPRs should also go up? As a technology aggregator, HP's products contain hundreds, if not thousands of inventions, patented by dozens, scores, or even hundreds of companies. There is a fragmentation of patent rights (self-link) in complex technologies which places pressure on the traditional approach to patent law. Reform may well be needed, but it is questionable if the Reform Act of 2007 addresses this problem in the right way. What is certain is that opaque corporate advocacy does little to advance the debate. Conflating the problem of "bad" patents with the high cost of infringement, as Mr. Clark does (and previously Intel's Bruce Sewell did) is misleading. The threat to big business, like Intel, comes from legitimate patents, duly and properly issued by the USPTO (and other patent offices.) Multi-billion dollar damage awards result from the refusal of infringers to accept a license when it is offered. (self-link) What the PRA does is make it significantly less expensive to infringe legitimate, useful patents. Whether this makes sense in the Knowledge Economy is something that the U.S. Congress must soberly consider. Patent Nonsense (permalink) Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Bruce Sewell, General Counsel for chipmaker Intel, urges Congress to pass the much debated U.S. Patent Reform Act of 2007, introduced as S.1145 in the Senate and H.R.1908 in the House. Observing that "the number of patent lawsuits nearly tripled between 1991 and 2004, and the number of cases between 2001 and 2005 grew nearly 20%" Mr. Sewell quickly proceeds to his bottom line:

The cost of infringement is going up. But isn't this expected? In industries where profits are derived from intellectual capital, intellectual property rights (IPRs) play a more dominant role in the realisation of these profits. There is certainly an abundance of empirical evidence to indicate that IPRs are assets of increasing business value. Isn't it to be expected that the cost of infringing these IPRs should also go up? (And let's keep this in perpective: Intel earned $87 bilion in the second quarter of 2007. A theoretical patent damage award of $100m against Intel would correspond to just over 1% of this quarterly amount.) As a technology aggregator, Intel's products contain hundreds, if not thousands of inventions, patented by dozens, scores, or even hundreds of companies - including (one assumes) Intel itself. There is a fragmentation of patent rights (self-link) in complex technologies which places pressure on the traditional approach to patent law. Reform may well be needed, but it is questionable if the Reform Act of 2007 addresses this problem in the right way. What is certain is that opaque corporate advocacy does little to advance the debate. Conflating the problem of "bad" patents with the cost of infringement, as Mr. Sewell does, is misleading. Whilst it is entirely true that "the number of questionable, loosely defined patents, moreover, is rising" this has little to do with the increasing number of claims being made by legitimate patent holders. Ironically, Mr. Sewell seems to make this point himself, mockingly referring to "[o]ne company[which] holds patents that it claims broadly cover current technologies that allow people to make phone calls over the Internet." The nerve of them. Mr. Sewell is obviously referring to Verizon and their portfolio of VoIP patents - which were recently upheld by a Federal District Court. In their suit against VoIP competitor, Vonage, Verizon asserted seven U.S. Patents: 6,430,275 Enhanced signaling for terminating resource 6,137,869 Network session management 6,104,711 Enhanced Internet domain name server 6,282,574 Method, server and telecommunications system for name translation on a conditional basis and/or to a telephone number 6,128,304 Network presence for a communications system operating over a computer network 6,298,062 System providing integrated services over a computer network, 6,359,880 Public wireless/cordless Internet gateway The jury found Vonage guilty of infringing three of these U.S. Patents 6,430,275, 6,128,304, and 6,359,880. It would seem a bit unfair to characterize such patents as "questionable" and "loosely defined." Verizon's patents came out of inventions developed at GTE Labs before the 2000 merger of GTE and Bell Atlantic. GTE "was the largest 'independent' US telephone company during the days of the Bell System." GTE Labs was a resepected research organisation. Comparing these patents to the matter of "a five-year-old boy [who] patented a method of swinging on a swing" is utterly absurd. Just because some patents are bad does not mean that all patents are bad. The threat of ten figure damage awards does not come from "questionable, loosely defined patents." Far from it. The fact of the matter is that 5 year old Steven Olsen of St. Paul Minnesota is unlikely to ever see any income at all from U.S. patent 6,368,227. This is fate of most patent holders. The difficulty of licensing intellectual property remains the real threat to innovation. The threat to big business, like Intel, comes from legitimate patents, duly and properly issued by the USPTO (and other patent offices.) Multi-billion dollar damage awards result from the refusal of infringers to accept a license when it is offered. (self-link) Software Patents in the UK - Part 2 of 3 Part I of this series looked at the way national courts of the EPC contracting states (in particular the UK) give weight to the EPC and decisions of the EPO's Boards of Appeal. In October, 2006 the Court of Appeal issued a decision in the matter of the appeal of Aerotel Ltd. and Telco, the matter of The Patents Act of 1977, and the matter of Patent Application GB 0314464.9 [2006] EWCA Civ 1371 (49 page pdf). As the commercial impact of patent decisions is what is most interesting to this blog, the matter of Aerotel Ltd. an Israeli company specialising in pulse to tone converstion products and Telco Ltd. one of the U.K.'s pre-paid telephony services. Aerotel and Telco were engaged in a infringement dispute over Aerotel's GB patent 2,171,877. The '877 patent

Sued for infringement, Telco counterclaimed to have Aerotel's patent revoked. In the revocation request, Telco argued that the claimed invention was not an inventyion for the purpose of the U.K. Patent Act of 1977 because it consisted of "a scheme, rule, or method of doing business as such." As Mr. Justice Lewison wrote;

A summary of the headnotes of the Hitachi case states:

In other words, the invention itself must be of technical character and not simply involved technical means. Applying this reasoning to Aerotel's patent, Mr. Justice Lewiston concluded that

The patent was revoked on May 3, 2006 EWHC 997 (Pat) (8 page MS Word format). The Court of Appeal took a different view of the matter. Looking aside from Hitachi and focusing on the system claimed in the patent the Court observed "the system as a whole is new", emphasising that "it is new in itself, not merely because it is to be used for the business of selling phone calls". The Court concluded emphatically that "the system is clearly technical in nature." On this basis, the Court of Appeal argued that the method claims were "essentially to the use of the new system" determining them to be "more than just a method of doing business." The Appeal of Aerotel was thus allowed. Part III of this series will focus on the examination guidelines issued by the IPO and the surrounding controversy. Software Patents in the UK - Part 1 of 3 (Permalink) The Register reports that five UK Companies have filed a legal challenge against the U.K. Intellectual Property Office's recently issued examination guidlines on software patents. The IPO's guidelines result from the October, 2006 decision by the Court of Appeals in the appeal of Aerotel Ltd. and Telco, the matter of The Patents Act of 1977, and the matter of Patent Application GB 0314464.9 [2006] EWCA Civ 1371 (49 page pdf). Before proceeding to the controversy regarding the IPO's examination guidelines, it will be helpful to review the Court of Appeals Decision. The decision is remarkable for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the way it illustrates how national courts of the EPC contracting states defer to the EPC and decisions of the EPO's Boards of Appeal. Writing for the Court of Appeals, Lord Justice Jacob explains firstly that the EPC is the equivalent of UK Patent Act.

Secondly, he underlines the importance of the EPO Boards of Appeal to UK Law:

Thirdly, Lord Justice Jacob explains the desirability for harmonisation amongst convention members in the interpretation of EPC and corresponding national law:

Moreover, he points out that such deference creates a bilateral obligation on the EPO Boards of Appeal, noting that:

This is very instructive. Apart from the EU's desire to create a community patent and a common court for patent litigation, there is already a strong motion within the members of the EPC to achieve harmonization. This speaks volumes about the existing "European" attitudes regarding patent law and practice and suggests the there may be less of a need for a Community patent than the EU Commission would have us believe. European patent law is becomign increasingly complicated and it may make good sense for the bureaucrats in Brussels to slow the rush to exclude national courts from participation. In particular, the work of the UK courts has (in this observer's humble opinion) provided a valuable contribution to the formulation of case law relating to patents. Part II of this series will discuss the details of the Court of Appeals Decision, Part III will present the impact of this decision on the new examination guidelines and the accompanying controversy. Microsoft Accuses FOSS of Infringing 235 Patents In an interview with Fortune Magazine Microsoft's General Counsel Brad Smith and "licensing chief" Horacio Gutierrez alleged that "FOSS infringes on no fewer than 235 Microsoft patents." Suggesting that the infringement is willful, Mr. Gutierrez asserted:

This is not the first time Microsoft has raised the spectre of a patent fight with Free and Open Source Software. Following Microsoft's patent cooperation agreement with Novell in November of last year, Microsoft's CEO Steve Ballmer told analysts:

Microsoft's announcement seems likely to benefit customers of Novell's SUSE Enterprise Linux who "receive directly from Microsoft a covenant not to sue" for patent infringement. Just last week Novell issued a press release stating that 12 new customers (1blu, Arsys, Fujitsu Services Oy, Gordon Food Service, Gulfstream Aerospace Corp., hi5 Networks Inc., Host Europe, Nationwide, PRISACOM SA, Reed Elsevier, Save Mart Supermarkets, and state of California, Department of Fish and Game) had come under the umbrella of their agreement with Microsoft. What Patents Are Being Infringed? As reported in Fortune, Microsoft asserts that:

Microsoft, however, so far refuses to specifically identify these patents "lest FOSS advocates start filing challenges to them." Why not? Shouldn't Microsoft want to know if any of its patents are invalid? Microsoft's lack of transparency on this is a bit troubling and does little to enhance the credibility of their annoucement. Certainly, U.S. Patent 6,594,674 "System and method for creating multiple files from a single source file" is is likely violated by every file compression tool such as tar, unzip, and Java. Microsoft's FAT patents are also likely included in the list of 235. The announcement casts a dark shadow over Dell's recent decision to supply its PCs pre-loaded with Ubuntu. Corporate users of Red Hat Enterprise Linux might also start feeling uncomfortable. It's Stealing Dammit Michael Kanellos writing in CNET News.com explaining why he "loves patents and copyrights" makes the best case for copyright I have ever read:

The Slashdot crowd responded with their usual misinformed comments in particular the old shibboleth that downloading a film without paying for it is not "stealing" in the literal sense of the word. Downloading hipsters believe that "stealing" only relates to physical property and only occurs when the owner of said property is deprived of said property. In the on-line world only cars, mobile phones, and iPods can be stolen. Downloading a copyrighted film over Bittorrent cannot be "stealing" since the copyright owner still has her original copy. This facetious word-play is supported by criminal statutes such as the Western Australian Criminal Code, Section 371 in which stealing is defined as "depriving the owner of the thing or property". On Nov. 22, 1968, Star Trek episode 65, "Plato's Stepchildren" aired for the first time on American television. Plato's Stepchildren was remarkable in that it included broadcast television's first interracial kiss - between Captain Kirk (played by William Shatner) and Lt. Samara Uhuru (played by the Nichelle Nichols). This was a landmark event for television. Whilst a white man kissing a black woman is be considered as a trivial event today, in 1968 - the same year Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated and Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists on the medal stand at the Mexico City summer Olympics - it was a very big deal. More than a few television stations in the then still-segregated American south refused to air the episode. As one of the first black women to appear in any significant role on a prime-time television program, Ms Nichols was tempted to leave the series during its first season. A conversation with Dr. King who told her she "could not give up.. for she was playing a vital role for young black children and women across the country." Ms Nichols went on to play in every episode of the original Star Trek. Residuals are "payments made to actors, directors, and writers involved in the creation of television programs or commercials when those properties are rebroadcast or distributed via a new medium." In the 1950's a number of unions, such as the Screen Actor's Guild, the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, the Writer's Guild of America, and the Director's Guild of America negotiated residual payments from the emerging television market. Residuals remain an important part of the compensation for creative talent. Born in 1932, Niclelle Nichols is far more than "some old lady" but if I were to download a copy of Plato's Stepchildren over Bittorrent (or any other peer-to-peer network) instead of buying a licensed DVD or watching a licensed re-broadcast, I would be depriving Ms Nichols (and everyone else associated with that episode) of some small amount of money she would otherwise earn from residuals. Considering that money is most certainly "property" by any definition, infringing the copyright on Plato's Stepchildren is stealing from Nichelle Nichols. Who would do such a thing? KSR v. Teleflex The Supreme Court of the United States issued its decision in the case of KSR v. Teleflex (31 page pdf). The question presented to the court related to the matter of "obviousness":

Since 1949, the guideline for USPTO examiners has been Graver Tank & Mfg. Co. v. Linde Air Products Co., 336 U.S. 271 (1949) which specifies a four-factor test for obviousness:

In the intervening years, the Federal Circuit,

In practice, the TSM test is has made it difficult for patent examiners to reject claims by restricting the prior art examiners were able to use to demonstrate obviousness. The result has been a spate of patents comprised of known building blocks lacking what European examiners know as "inventive step." Without inventive step, most inventions would be just new combinations of known elements. Writing for the majority, Justice Kennedy observed that:

Rejecting the Federal Circuit's "rigid" application of TSM, Justice Kennedy argued:

The court did not reject the TSM test outright, but it rejected the Federal Circuit's rigid application of it. The impact of this decision remains to be seen, but it is generally accepted as raising the bar for patentability (and throws into doubt the validity of countless patents already issued by the USPTO.) The USPTO issued a memo (2 page pdf) on the decision and promises to provide updated guidelines in the near future. This decision, along with the Roberts' court other patent decisions (AT&T v. Microsoft, MercExchange v. eBay, MedImmune v. Genetech) appear entirely consistent with a Supreme Court that is bringing the Federal Circuit back into the mainstream of American jurisprudence. Microsoft v. AT&T The U.S. Supreme Court has issued its decision (31 page pdf) in the matter of Microsoft v. AT&T concluding:

The SCOTUS decision overturns the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) decision that Microsoft should be held liable for patent infringement on copies of the Windows operating system sold outside the United States. In the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court's 1972 decision in Deepsouth Packing Co. v. Laitram Corp. 406 U.S. 518 the U.S. Congress (in 1984) amended 35 USC 271 to broaden the definition of infringement.

Writing for the majority, Justice Ginsburg observed:

With regard to the former, the SCOTUS differentiated between software as an intangible, abstract, set of instructions and a physical copy of the software code concluding that "a copy of Windows, not Windows in the abstract, qualifies as a component under §271(f)." With regard to the second question (i.e., has Microsoft "supplie[d] ... from the United States" components of the [infringing] computer involved?") the court succintly concluded the answer to be "No." The parties reached a confidential settlement in 2004 for domestic sales. The matter of liability for exported code is no longer in dispute: The lesson for patent practitioners is clear:

Dennis Crouch at Patently-O and Cornell Law School have nice backgrounds on the case. Hedge Funds Fueling Patent Litigation Forbes Magazine reports that "hedge funds and institutional investors are financing the latest wave of IP lawsuits." Forbes highlights the marriage between Altitude Capital Partners and DeepNines in DeepNines' patent infringement litigation against McAfee and observes that ACP has

Describing this development in ominous tones, Forbes cites the "threat of war" and notes the similarity to patent trolling "a much-vilified practice." Of course, the entrance of private equity into the market might also be seen as solving the problem of asymmetrical litigation costs (9 page pdf) which can be used by large, incumbent companies as an entry deterrence instrument against smaller competitors. The increasing costs of U.S. patent litigation (estimated in the 2005 AIPLA Economic Survey $4.5m in cases where damages exceed $25m) and the attraction of significant infringement damage awards ($612m in RIM v. NTP, $1.5b in Alcatel-Lucent v. Microsoft) has created an enviroment of mutual interest between patent holders and private equity. There can be no doubt that the influx of capital will make its impact felt on the business of IP. EU Commission Supports Rapid Introduction of a Community Patent In a speech (transcript) to the European Patent Forum honoring the European Inventors of the Year, Günter Verheugen, Vice-President of the Commission called for rapid action on the London Agreement and the Community Patent to improve protection of intellectual property rights in Europe "wie wir alle wissen - immer noch stark fragmentiert ist." The lack of a community patent and the existing demands for translation into all languages of the EU make obtaining patent protection across the European Union significantly more expensive than in other regions of the world.

Ratification of the London Agreement which outgoing EPO President Pompidou predicted would be completed by France "by the end of this year" would significantly reduce translation costs by waiving, "entirely or largely, the requirement for translations of European patents to be filed in their national language." The EU Community Patent which was again endorsed earlier this year by Internal Market and Services Commissioner Charlie McGreevy would create a single, community-wide patent. This however, along with the European Patent Litigation Agreement (EPLA), an integrated EU-wide jurisdictional system for patents, appear to remain much further out on the horizon. It would seem that assertions by the IPR community that the fragmentation of IPR protection in Europe puts European companies at a disadvantage are perhaps overstated and more than likely self-serving. In a global business environment, the European fragmentation of IPRs affects all companies (European and non-European) doing business in Europe more or less equally. What lack of a community patent and EPLA does is make the EU a slightly less attractive place for conducting R&D and a far less attractive forum for resolving IPR disputes. The latter's effect on European patent attorneys and litigators is palpable. Linux: a patent-tax-free alternative to Windows? Marking the annual celebration of tax season in the United States, the Software Freedom Law Center (SFLC) has issued a statement (2 page pdf) notifying taxpayers that if they are using Microsoft's Windows Operating System, they are also "paying a hidden tax of well over $20 that Microsoft has had to pay to other patent holders." The SFLC estimates that Microsoft has incurred more than $4,3b in patent-related costs (legal fees, settlements, damages, etc.) over the past 3 years. Dividing this figure by the number of Windows users, the SFLC arrived at its estimate of the "tax" Windows users are paying. Users of the Linux-kernel based Open Source Operating Systems, the SFLC observes, pay no patent tax whatsoever: Another way of looking at this is that Linux users may not have a license to use all the patented technology incorporated into the Linux-kernel (and its derivative Operating Systems). With the increasing proliferation of patent-infringement lawsuits, it seems hardly reassuring to remind Linux users of the "patent" risks of using Linux. The fact of the matter is that it is highly unlikely that Linux is free of patent infringement. Indeed, as ITWeek noted:

Because of the "patent tax", Windows users have some confidence that their use of the Windows OS will not make them patent infringers. Without any mechanism to acquire the patent licenses which are increasingly necessary to achieve interoperability, Linux users remain at risk. EPO Boards of Appeal Decision T 1023/06: Computer Implemented Game Process In its decision T 1023/06 (20 page pdf) the EPO Boards of Appeal refused the application of International Game Technology (NYSE: ITG) for a patent on A Computer Implemented Game Process. The decision illustrates some interesting aspects of how the EPO deals with so-called Computer Implelemted Inventions (CII). In October 2005, the EPO's Examining Division refused IGT's European Application No. 98 113 910.8 on the basis that the application did not meet the requirements of Article 52(1) in combination with Article 56 for lack of inventive step having regard to a prior art U.S. patent. In their appeal, IGT argued that an additional, inventive step was present in their claim which distinguished their invention from the prior art and that this additional step served "a clear technical function." The EPO Board of Appeal noted:

According to EPO practice, in the situation where an invention contains a mixture of technical and non-technical features, inventive step is assessed by taking into account of all those features which contribute to the technical character. (T 641/00, OJ EPO 2003, 352 - 13 page pdf). There is however an important caveat to this: features making no contribution to technical character cannot support the presence of inventive step. In other words, the invention must make a "technical contribution". The EPO uses a well-established method for determining whether or not a claimed invention makes a technical contribution which follows the problem-solution approach outlined in the Guidelines for Examination. Firstly, the examiner first establishes the difference between the closest prior art and the claimed invention and uses this to define the problem to be solved. Secondly, if the problem and the proposed solution seen as a whole belong to a technical field or are not excluded under Article 52(2) then the invention may be considered to have a technical character. In rejecting IGT's application, the Board concluded:

Commission sets out vision for improving patent system in Europe The EU Commission announced the publication of a communication of the Commission's proposal to enhance the patent system in Europe (22 page pdf.) Last week at the EU Presidency/BDI Conference "A Europe of Innovation - Fit for the Future?" Charlie McCreevy, European Commissioner for the Internal Market and Services, expressed some doubt over the future of EU patent policy. The Commissioner's remarks (4 page pdf) are a bit confusing. He begins by discussing the well-known problem of costs of obtaining patents in Europe,

As the commissioner well knows the problem lies not with the EPO, where "it currently costs on average EUR 4 600 to take a patent with seven or more designated states to the grant stage." The problem lies with the post grant procedures. Because patents granted by the EPO must be indivdually registered and translated in each national patent office, according to a study published last year by the EPO, it costs on average ¤32.000 ($38,000) to obtain a European patent registered in six European countries. (A breakdown of USPTO and EPO costs is shown here.) It is less clear that Commissioner McCreevy knows with whom the problem does lie. It is not at all clear that a solution offered by the EU Commission is desirable, or even necessary. The European Patent Convention is still a valid treaty. The London agreement on the application of Article 65 EPC, the EPO's 2000 legislative initiative to waive, entirely or largely, the requirement for translations of European patents to be filed in their national language, remains mired in debate, but would receive a lift if the EU Commission would give a green light to its efforts. There cannot be much anticipation of success in having the Commission deal with this matter. Two other major legislative initiatives also launched in 2000: EU Community Patent and the European Patent Litigation Agreement (EPLA) also remain no closer to consensus. Add to this backdrop, the Commission's failed 2004 Directive on the patentability of Computer Implemented Inventions and the future for reform looks bleak. Nevertheless, Commissioner McCreevy explains why the Commission will focus on the EPLA:

As the Commissioner noted in his remarks "... the patent dossier is a very tough nut to crack." In annoucing his new legislative intiaitive, Mr. McCreevy explained:

The problems addressed bv the patent dossier are real; it is the solutions which have proven presistently elusive. Inventors in Europe can only hope that the Commission's newest attempt doesn't turn into yet another disappearing act. |

Note: This site is under continuous construction. New material is added frequently. Some links may be inactive and some may fail (often only temporarily) without warning. News items are added regularly depending on events and your commentator's workload. Old news items are placed ced here in the archive. Embedded external links may expire and I may also delete/edit items in the archive without warning. I apologize for any inconvenience. This website contains general information relating to patents and other intellectual properties and is presented for informational purposes only. Nothing herein is offered as legal advice. |

Avvika Aktiebolag

www.avvika.com |